A History Of Sundials: How Shadow Clocks Mark The Passage Of Time

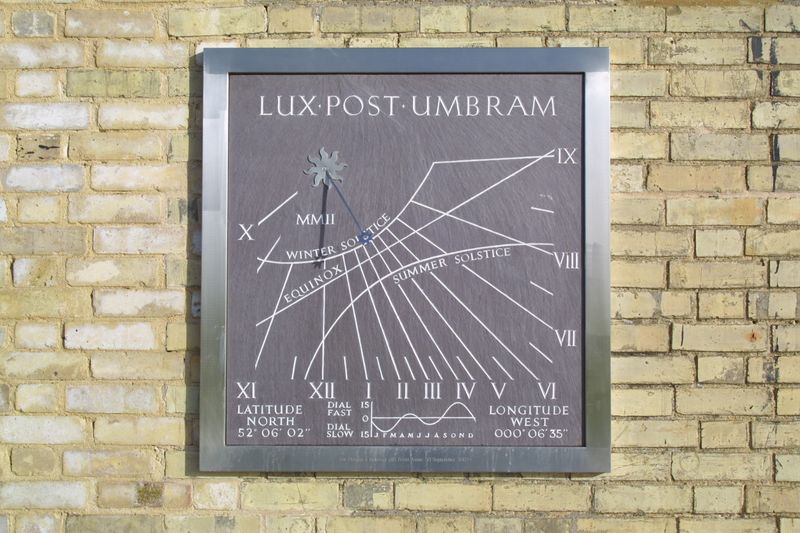

For thousands of years, long before the invention of mechanical clocks, humans looked to the sky to measure the passage of time. Among the earliest and most enduring timekeeping tools is the sundial – a scientific instrument that uses the position of the sun to indicate the time of day. In its simplest form, a sundial consists of a flat surface, known as the dial plate, marked with hour lines and a raised arm or stick called the gnomon, which casts a shadow across the dial as the sun moves across the sky.

The origins of sundials can be traced back to the ancient Egyptians, who first divided the day into segments using simple shadow-casting devices. Over time, sundials evolved in complexity and precision with equatorial and horizontal designs becoming common across cultures.

The angle and placement of the gnomon are carefully calculated to align with the Earth’s axis, allowing the sundial to track solar time accurately throughout the year for its exact location. Even accounting for the changes marked by the equinoxes – when daylight and night have equal hours – and solstices.

The classic look of the sundial is enhanced by its engraved Roman numerals

The timeless elegance of the armillary sphere makes it a highlight at events

Seeing, understanding and engaging with the hours of the day on a sundial is a different experience on a phone, watch or clock. It’s inexorable and the observer is at one with that moment in time.

A brief timeline of the sundial

c. 1500 BCE – Ancient Egyptians

The Egyptians are among the earliest pioneers of timekeeping. They used simple shadow clocks – early sundials – to divide daylight into parts. These devices laid the groundwork for future developments in solar time measurement.

c. 700 BCE – Babylonian innovations

The Babylonians refined sundial techniques, incorporating astronomical observations and advancing the understanding of the azimuth – the sun’s angle in relation to true north.

c. 500 BCE – Ancient Greeks

In Greece, philosophers, astronomers and mathematicians developed more sophisticated sundials, introducing the use of latitude-specific gnomons and hour lines. The Greeks also connected sundials to their broader study of geometry and astronomy.

c.100 BCE – Roman sundials

The Romans adopted and popularised Greek sundials throughout the empire. In Rome, sundials became both practical tools and public monuments, spreading the art of solar timekeeping across Europe.

14th century – Observatories and Islamic scholars

In the Islamic world, observatories flourished. Scholars built precision sundials and even incorporated them into complex instruments like the armillary sphere to aid in both timekeeping and celestial navigation.

18th century – The age of scientific instruments

As scientific thought advanced, sundials were crafted with extraordinary accuracy and beauty. They became prized instruments of horology; even as mechanical clocks became more prominent.

Modern use of sundials

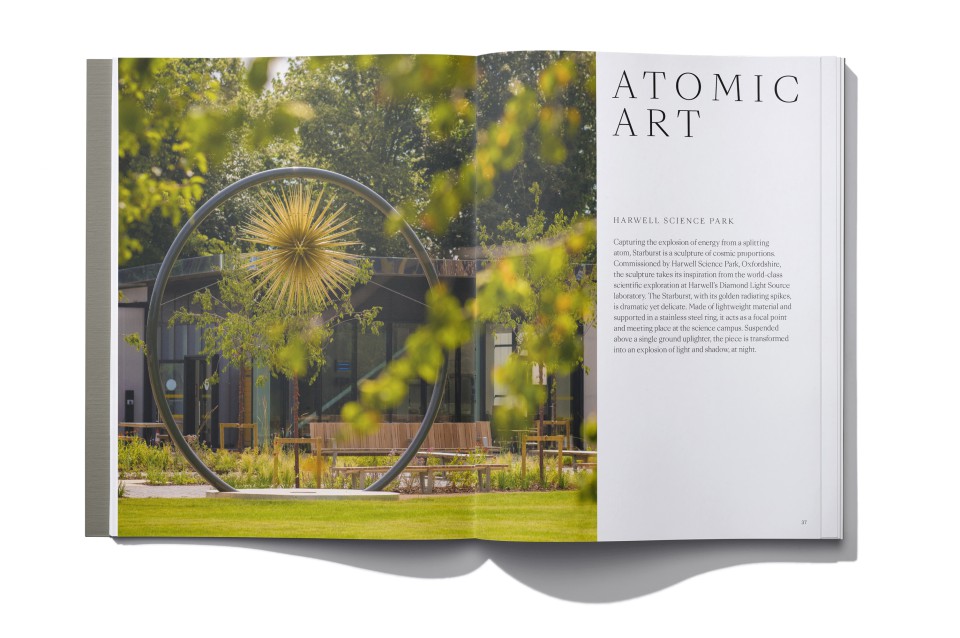

Sundials have been carved into stone, forged from bronze and have even been used in the Arctic Circle and on Mars! Though no longer essential, they are a reminder of human curiosity, ingenuity, and our age-old fascination with the sun and the heavens.

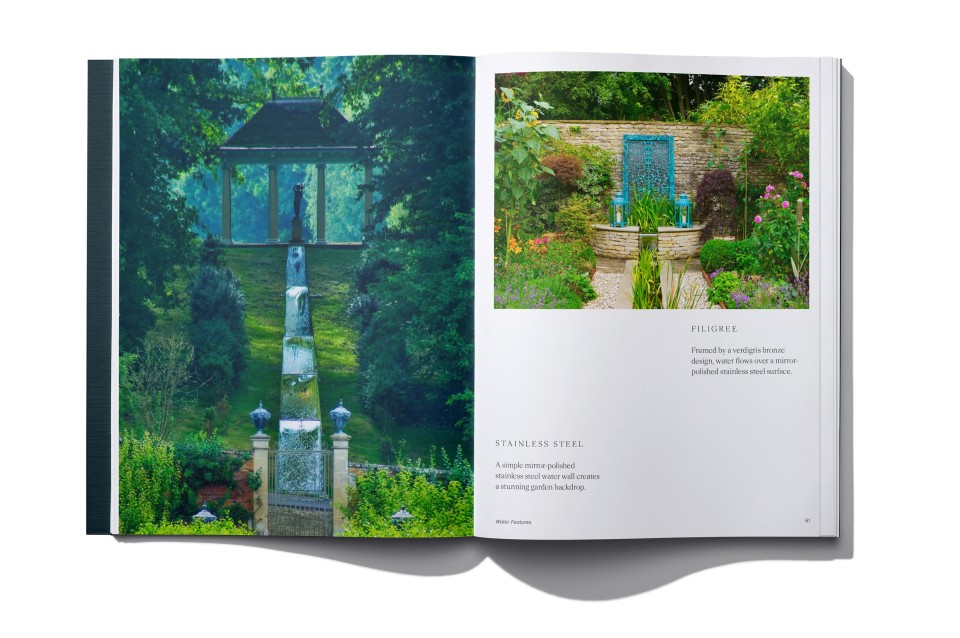

Historic sundial designs made for the modern age

Sundials are more than relics; they represent the foundation of horology and the enduring human fascination with celestial rhythms. Their study offers insight into the ingenuity of early science and our ongoing relationship with the natural world.

David Harber's careful attention is focused on ensuring the armillary's quality

David Harber’s first artwork was a sundial, an Armillary Sphere. And as the business has grown, so too has our portfolio of sundial designs, each measuring time in its unique way.

“Sundials set time and clocks keep time.”

Alfred Gatty

Types of sundial

Vertical sundial

Setting the pace of public life in the ancient world, vertical or horizontal sundials would indicate the changing seasons, sunrise and sunset and prayer times. Sir Christopher Wren is just one of many architects to have taken on the three-dimensional challenge of the vertical dial – latitude, longitude and ‘declination’ to the ecliptic – orientation from due south.

Armillary sphere

One of David Harber’s earliest and most appreciated works, Armillary Sphere is calculated and crafted to its intended location, making it a highly accurate timepiece. Invented by Greco-Roman astronomer Ptolemy nearly two millennia ago, the armillary sphere has been interpreting the movements of the heavens ever since.

Obelisk

With its clean, crisp architectural lines, the Obelisk is an instantly recognisable and striking focal point. Historically used to demarcate the entrance to tombs or temples, astronomer-mathematicians in Ancient Egypt used the obelisk’s daily sweep of shadow lengths to document seasonal progression, with the shadow expanding on the winter solstice and retracting on the summer solstice.

With great precision and care, the armillary has been crafted to a flawless standard

Interested in crafting your sundial?

David Harber specialises in designing and crafting sundials. We believe sundials are about time and place, the people that commission them and the sentiment they convey. They can be shared with future generations as heirlooms, a message to pass down through the ages. If you’re interested in commissioning a sundial, email enquiries@davidharber.com.

Related articles

The magic of conversation

Whether you’ve decided on a piece or you just want to sound out an aspect of our work, please get in touch with our team to discuss your needs.